From Emily Bronte to Bill Moyers, authors have used the phrase “the ties that bind” to describe a strong link between two items. This post highlights the historic railroad ties—both mechanical and human—that bind Mount Desert Island and Cadillac Mountain (formerly Green Mountain) to the northeast’s tallest peak, Mt. Washington in New Hampshire.

Mechanical Ties

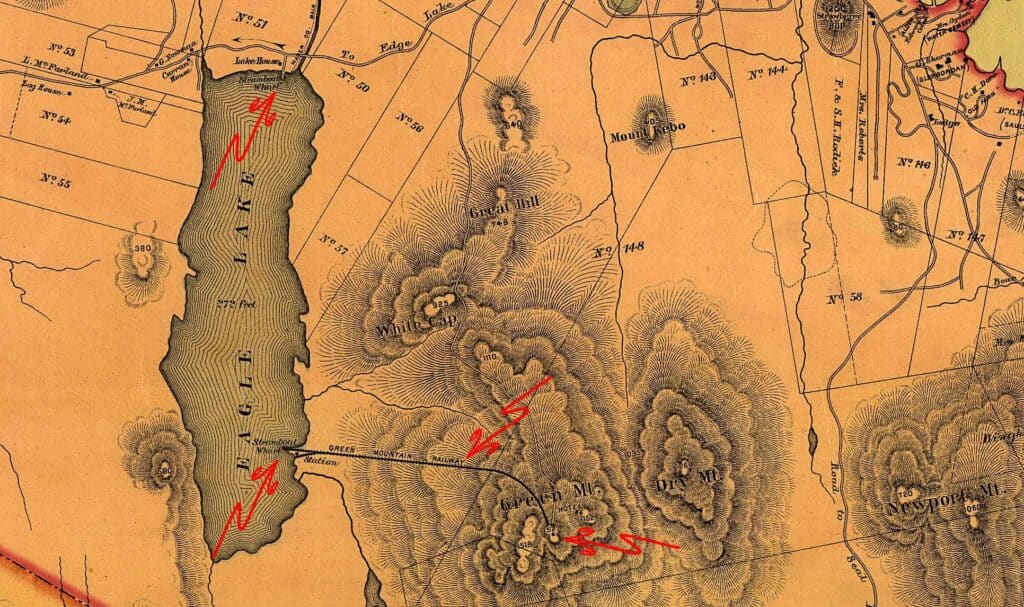

Maine entrepreneur Francis H. Clergue developed a narrow-gauge railway from Eagle Lake at the base of Green Mountain to a hotel at its summit. He chose to model his Green Mountain Railway (GMR) trains and track on Sylvester Marsh’s 14-year-old railway that had conquered the heights of Mt. Washington.

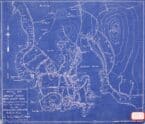

Clergue had two GMR locomotives built. The first, Green Mountain, was used in 1883 to construct his railroad using the same cog gear arrangement Marsh had designed for Mt. Washington. The cog gears of the engine meshed with a center rack rail (see photo), however, unlike in New Hampshire the railway ties holding the centerpiece and the side “T”-rails were not supported by extensive and expensive wooden trestlework. Instead, under the direction of Frank W. Cram of Bangor, workmen bolted the ties to the rock ledge found along the 1.2-mile route. The Maine Railroad Commissioners described Clergue’s new tourist railroad this way:

The Green Mountain Railway was chartered and built in the spring of 1883 for the purpose of providing a safe and convenient conveyance for visitors at Mount Desert to ascend to the summit of Green mountain and obtain a view of the magnificent ocean and mountain scenery, only to be seen and fully appreciated by ascending to the top of this famous mountain. Before the construction of the Green Mountain Railway the ascent was made on foot or by buckboards, over rough and dangerous mountain roads; now the buckboard is used only to convey passengers to the foot of Eagle lake and from thence they are taken by steamboat about two miles to the railroad station on the shore of the lake. At the examination of this road, in the early summer, the commissioners were convinced that it was securely built and worthy of the entire confidence of the public.

June 23, 1883

Clergue initially figured he could meet demand by running four Green Mountain trains per day, delivering passengers to the mountaintop hotel, but soon six trips were run and still people were left behind. By the end of August 1883, the never-named* No. 2 engine was ordered. With a second train on the tracks, the summer of 1884 looked bright to Clergue. Then, the hotel burned. And Clergue’s effort to extend a narrow-gauge railway 3 miles from Bar Harbor to the terminus of the GMR ran into public opposition. His petition for the connecting railroad was denied by the Maine Railroad Commissioners.

Clergue’s mountain-climbing railway is well documented in Peter Dow Bachelder’s 2005 book: Steam to the Summit: The Green Mountain Railway — Bar Harbor’s Remarkable Cog Railroad. Remarkable? Yes. Profitable? No. The GMR carried 1,305 passengers during the 1889 summer season and brought in $2,154.10 ($63,615 today) with just seven employees. But its expenses totaled $5,182.56 ($153,052 today) and it was running a deficit of $12,434.20 ($367,209 today). The GMR would not last into 1891. On August 1, 1891, the Chicago Tribune reported, “The Green Mountain railway is not yet in operation this year, but the carriage road (up Mt. Desert) is doing a good business. People generally prefer the carriage drive up the mountain to the ascent by rail.”

See and read more about MDI’s railway in the Digital Archive

- “Green Mountain Railway,” an article by Frank Matter.

- “Green Mountain Railroad: An Experience Not to Forget,” a student article by Jessica Sattler.

- “Green Mountain Railway,” an article by Richard F. Dole.

Fire on the Mountain

On the morning of May 23, 1895, one work train was sent up Mt. Washington with a crew to prepare the summit hotel for opening; another crew was dealing with a fire burning near the rail line. A third engine at the Base was under steam and four other locomotives sat cold in the roundhouse.

In the afternoon, the roof of the wooden depot where railway workers slept was spotted burning. The wind was blowing very hard from the direction of a forest fire on Mt. Dartmouth and the theory was that embers had traveled the 3 miles to ignite the roof. Flames quickly spread. Fire destroyed nearly the entire complex—the two-story station, car house, engine house, water tank, machine shop and laundry, along with three passenger cars and three locomotives: Falcon, Tip-Top and Pilgrim. Workers lost clothing and money. Only a woodshed and the Marshfield House hotel built upon a nearby bluff were left standing. The loss was estimated at $30,000 ($970,000 today), and, the summer season was due to start in a little more than a month.

Peter Dow Bachelder explains in Steam to the Summit how Mount Desert Island provided a lifeline. The owners of the Mt. Washington railway soon learned “that the two Green Mountain Railway locomotives were languishing at the foot of Green Mountain. Within ten days, the company had purchased the idle ‘iron horses’ and arranged to have them partially dismantled, to facilitate their shipment via the Maine Central Railroad from neighboring Mount Desert Ferry to Mount Washington. Although extensively rebuilt over the years, to the extent that few, if any, original parts remain, the two former Green Mountain Railway locomotives are still operating on Mount Washington.” Since publication of Bachelder’s book in 2005 both have been retired.**

Human Ties

Clergue (pictured in 1895) and Marsh were the Bezos and Branson of the late 19th century seeking to take tourists to soaring heights via new technology (though perhaps not as well capitalized). The number of people with the skill set and expertise to operate such cutting-edge technology in the late 1800s was small, so veterans of the first mountain-climbing railroad in New Hampshire were in demand!

Forty-one-year-old engineer Albert S. Randall, who had started at Mt. Washington during its founding year of 1866, was running an engine on Green Mountain in 1884. He came back to New Hampshire in late July reporting “a light summer business at the summer resorts along the Maine coast.” That didn’t deter 32-year-old engineer Jack McCarthy and 27-year-old fireman Fred Pillsbury from heading to Maine in August “to run on the Green Mountain Railway.” Pillsbury came back to Mt. Washington, but McCarthy did not. Mae D. McFarland’s 1933 recollection of the Green Mountain Railroad says engineer Jack McCarthy was one of the “names to be recalled.” He and his wife lived in Bar Harbor and McCarthy worked as a carpenter when not running steam engines.

Big, Busy & Brusque

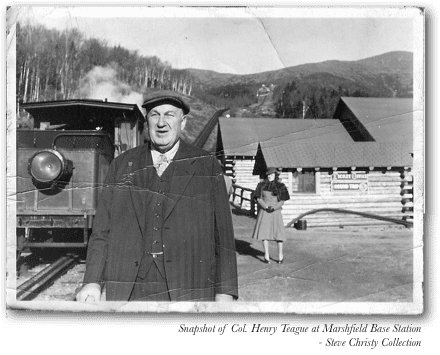

As Clergue’s GMR was getting underway, a local lad of 11 was beginning his life-long career in the tourist trade (eventually running hotels in New York City, Miami, Williamstown, Massachusetts, Mount Kineo, Maine, and atop Mt. Washington.) Henry Nelson Teague was born on Mount Desert Island on June 2, 1875, the youngest son of Capt. George Edward Teague and Martha Cornelia (Dunham) Teague. The Bar Harbor Times would note, “Teague was the first bell-boy employed by the Kimball House in 1887 when he was 11 years old.” With nine children, George and Martha had turned a public dance hall in Manset into a family home.

Henry and his older brother, Edward Fisher Teague, followed their uncle into the hotel trade. Nathaniel Teague Jr., the uncle, owned and ran hotels in Maine, including the Ocean House and Cottage in Manset. By 1931, 56-year-old Henry had both boomed and busted in the hospitality trade since graduating from Dartmouth in 1900 and the first Tuck Business School class in 1901. He ran Dartmouth’s Dining Association, the New Weston Hotel in New York City, leased the Greylock Hotel in the Berkshires for 17 years, and added the Miramar in Miami to his portfolio in 1922. When Florida’s real estate investment bubble burst, the Tuck-trained Henry kept investing, banking on a turnaround that did not come. He was forced to declare bankruptcy in 1930 owing more than $230,000 with assets of just over $40,000; his final $42 was made up of a $15-dollar set of golf clubs and $27.50 in cash. However, Henry Teague’s well-known business boosterism and promotional skills prompted his colleagues of the New England Hotel Association to hire the “State of Maine Democrat” to run their jointly owned Landlord’s Inn at Templeton, Massachusetts.

Around that time, the then-owner of the tourist operation on Mt. Washington, Boston & Maine Railroad, asked White Mountain hoteliers whether they’d like to form an association and buy the Cog Railway. The Crawford House’s Col. William A. “Billy” Barron emphatically said “No!” Instead, Barron suggested the B&M should find “a circus promoter; a man who can run the road, increase services, stir up new business, publicize the railway to get more people interested in taking the trip up Mountain Washington.” Barron said, “Henry is a real promoter, and he has energy enough to do the job as it should be done.”

Thus, in 1931, Henry Teague was running the Mt. Washington Cog Railway and the Summit House. Teague turned a profit his first year at the helm as noted in a Concord Daily Monitor & New Hampshire Patriot profile headlined—”Big, Busy & Brusque.”

Brusque describes Henry Teague best of any single word. He shakes your hand in greeting and the next moment he may have thought of something else and he turns to do it. And then he turns back to you with a “pardon my abruptness” said briskly. And if you know him, you know his mind is at once on something else. You don’t mind the brusqueness, unless you are especially sensitive, for his way is one of non-affectation, and almost everyone likes a man who is natural—who is himself.

Over the years, Henry Teague increased the number of trains, began using college student crews, and oversaw installation of switches to boost the number of trips as well as technical improvements to the locomotives. When he died in October 1951, his body was brought back to MDI and buried in the Mount Height Cemetery—up the hill from his boyhood home—alongside his mother Martha, his uncle Nathaniel, and a stone to memorialize his father, George, who had been lost at sea when Henry was 2 years old. In true Henry Nelson Teague fashion, they all rest in Plot #1 on the inner circle.

* A November 1981 article by John Hilton in The Shortline: The Journal of Shortline and Industrial Railroads says Clergue ordered two engines and they were both delivered that first year of operations and the No. 2 was called Green Mountain. Bachelder’s 2005 Steam to the Summit says the second engine was ordered at the close of the first season and was never named. More research appears needed.

** Eight years after Clergue’s engines from Mount Desert came to the rescue of Mt. Washington, a 1903 New York Tribune story reported one of his Green Mountain Railway passenger cars was still in use “as a cobbler’s shop in Bar Harbor.”

- Header photo, Engine No. 2: “Passengers and crew are waiting to take the Green Mountain Cog Railroad to the summit of Green Mountain (now known as Cadillac). This Cog Railroad is very similar to the Cog Railroad in New Hampshire. Circa 1890.” Courtesy National Park Service, Acadia National Park, at Maine Memory Network (www.mainememory.net/artifact/21320 : accessed 26 October 2021).

- Green Mtn. track: “Green Mountain Railway,” Northeast Harbor Library, …view digital archive item

- Green Mtn. hotel: “Green Mountain House – New and Open for Business.,” Southwest Harbor Public Library, …view digital archive item

- Map segment: “1887 Map of Mount Desert Island, Maine,” Southwest Harbor Public Library, …view digital archive item

- “Portrait Francis H. Clergue“: Canadian Museum of History, courtesy Sault Ste. Marie Museum (digitalmuseums.ca : accessed 26 October 2021).

- “Sanpshot of Col. Henry Teague”: As presented at Mt. Washington Cog Railway: The Jitney Years (coggersofmtwashingtonnh.org : accessed 4 August 2021), courtesy Cogger Steve Christy (1966-1973) Collection.