The idea of nature contains, though often unnoticed, an extraordinary amount of human history.

Raymond Williams [1]

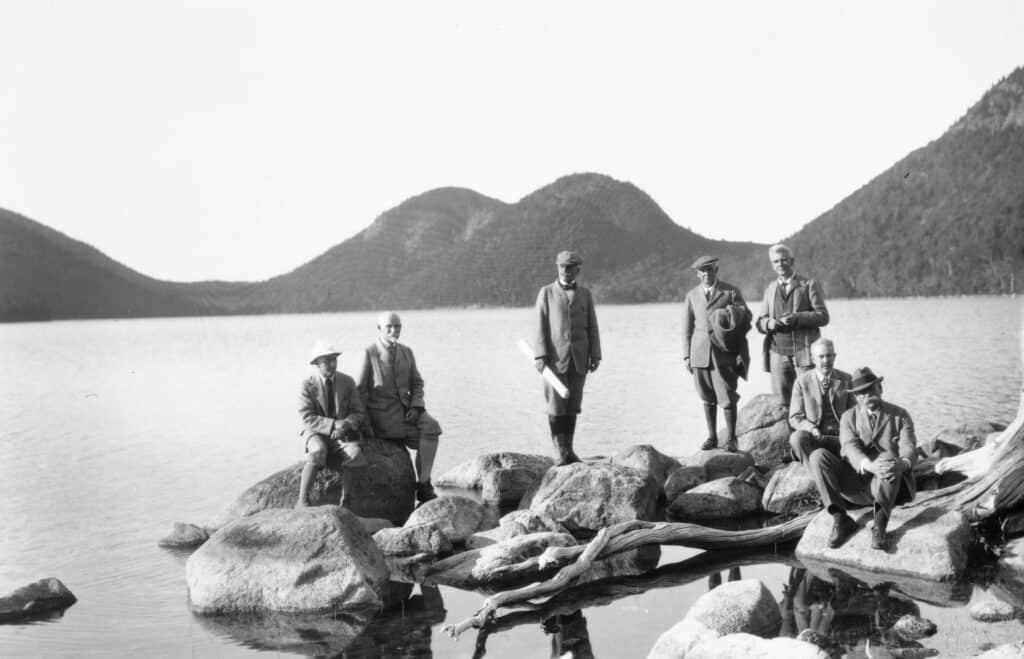

In creating The History Trust, we took lessons from the founders of the land conservation movement. Particularly, those who recognized the need to protect the exquisite qualities of Mount Desert Island by placing private properties into a public trust. Those lands, first held in trust by the Hancock County Trustees of Public Reservations, became Acadia National Park.

Like the extraordinary lands that became the national park, the region’s historical archives are irreplaceable and vulnerable public resources that should be protected and shared with the community by responsible stewards.

The hopes and intent of those 19-century voices that advocated for the conservation of wildness and landscapes included the artist George Catlin, Henry David Thoreau, Frederick Law Olmsted, John Muir, Theodore Roosevelt, and notable to us on Mount Desert Island, Charles W. Eliot.

Those visionaries hoped that a forward-thinking United States of America with a staggering abundance of natural resources and visual wonders, through stewardship, would preserve these places in trust for the people, for all the people. What have we learned from them? What have we done to conserve our natural history and heritage?

And from the historian’s perspective, what will we do to conserve our human historical heritage? Can we who are passionate about history emulate the past accomplishments of the land conservation community in passing that history, improved, to future generations?

What Natural and Human History Have in Common

Academic historians increasingly recognize that natural and human history are inexorably intertwined. To this point, William Cronon says, “Our project must be to locate a nature which is within rather than without history, for only by so doing can we find human communities which are inside rather than outside nature.”[2]

Cronon, and others, point out a sharp contrast in land practices between Native peoples and Europeans during the period 1600 to 1800. In short, their conceptualization of resources as common vs. commodity. European colonists perceived resources as “filtered through the language of commodities, goods which could be exchanged in markets where the very act of buying and selling conferred profits on their owners.”[3]

Is history a commodity that someone can own? Or are we merely its stewards? If we accept that current thought argues for the confluence of natural and human history, how can this new vision change our former ways of thinking about history?

If we can agree that history is not a commodity but a natural and common resource that is held in trust, imagine the public benefit if the trustees follow a common pathway; if old habits could be reshaped and newly defined.

Stewardship on MDI

As we model a history trust after what has already been applied to land, nature and natural resources, we need look no further than our own Mount Desert Island’s history to find an example.

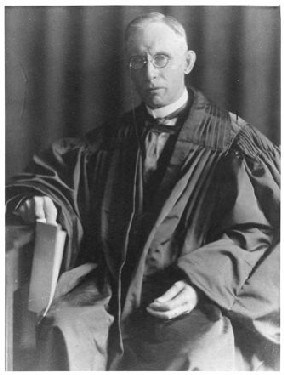

On the afternoon of August 22, 1916, the public gathered at the Building of the Arts near Kebo in Bar Harbor, Maine. The occasion celebrated President Woodrow Wilson’s July 6 proclamation to establish the Sieur de Monts National Monument, a crowning achievement of land conservation on Mount Desert Island brought about by the organization called Hancock County Trustees of Public Reservations. Several of the original corporators spoke that day, including Charles W. Eliot and George B. Dorr, but perhaps the most eloquent voice was that of a local attorney and judge, the Honorable Luere B. Deasy, who said,

The establishment of this monument guarantees that it will be perpetually open for the use of the public… not as a matter of suffrage but as a matter of right …. That these mountains, standing at the very edge of the continent, looking out across the ocean far beyond our country’s domain, should remain in private ownership, bought and sold by metes and bounds and used for private gain, is incongruous. That they should be held by the nation in trust for all its people is their appropriate destiny.

Photo: “Luere Babson Deasy,” Great Harbor Maritime Museum …view iteM

Deasy was careful to emphasize the words right and trust. And in his final sentence, we have a clear expression of something called the “public trust doctrine,” which holds that certain public resources are so essential to the public weal as to be incapable of alienation. The doctrine has its roots in the Roman and English concepts of res communes, the notion that certain property was held by the crown for the benefit of all the people.[4] Conceptually, the word trust has an inevitable connection with property or land. Witness the number of voluntary conservation easements entered into between willing property owners and local land trusts here in Maine. But what of other meanings of property, such as resources like air and water, elements falling under the general notion of “the commons”? How might these principles apply to the more abstract commons of history?

Consider the idea that history, like land, is a form of property that falls within a public trust doctrine: certain resources—in this case, history—are preserved for public use, and that the government—that is, historical resource holder—is required to maintain them for the public’s reasonable use.[5]

Land preservation is a useful model for history preservation. History is no less precious a resource than is land. Furthermore, our collective stories breathe life into and give abundant meaning to the land. Like land, history should be conserved, in trust, as a matter of right for the public. Stewardship is a core value in both land and history preservation.

For the past decade, individuals and organizations have worked together to fulfill a dream, first as the Friends of Island History and now, the History Trust. As in all collaborative efforts, the work has required patience and diligence. The result is in part what you see on this website, a central resource and archive that arises from a new relationship among organizations whose communities touch the waters of Frenchman and Blue Hill Bays. This is for you to enjoy.

~ Header photo: “A gathering at Sieur de Monts Spring, circa 1920.” Courtesy National Park Service, Acadia National Park.

Notes

This post is a condensed version of the article “The History Trust” published in the 2016 edition of Chebacco (Vol. XVII).

[1] Raymond Williams, “Ideas of Nature,” in Culture and Materialism (New York: Verso, 2006), 67.

[2] William Cronon, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England (New York: Hill and Wang, 1983), 15.

[3] Ibid., Kindle edition, location 2998.

[4] Mark Squillace, “Common Law Protection of Our National Parks,” in Our Common Lands: Defending the National Parks, ed. David J. Simon (Washington, DC: Island Press, 1988), 96-99.

[5] “Public Trust Doctrine,” accessed July 14, 2015, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_trust_doctrine.